Adaptive Listening™

Build trust and traction

Uncover a better way to listen that goes beyond active listening and paying attention. Learn about the way you prefer to listen, and adapt to meet the needs of others.

“Rhetoric may be defined as the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion. This is not a function of any other art.” – Aristotle

As business leaders, every day involves convincing someone of something. But did you know that upstream of every email, pitch deck, and crumb of small talk lies a singular term? Whether through written or spoken means, the decisions you make in how to communicate are a function of rhetoric. The structure of an email, pace of presentation, even the information you choose to share (or not share) with co-workers are all rhetorical choices.

At a high level, rhetoric is the source and lifeblood of purposeful communication. This may be conjuring up hazy memories of stuffy English classes. If so, take this as your cue to dust off that prior learning with fresh eyes. Understanding how to name and think about rhetorical decisions is crucial to being an effective communicator.

To bring balance and promote peace, samurai study the blade. To be equally formidable as writers and speakers, communicators should study rhetoric. But first, let’s clear the air on what rhetoric is and why it’s important.

“Rhetoric is the art of ruling the minds of men.” – Plato

Imagine wanting to build a new bookcase without the word ‘carpentry.’ Or loving to cook without ‘culinary’ or ‘cuisine’ to elaborate on that passion. Beyond expanding one’s vocabulary, drawing connections between words and their associations increases our understanding of their nuance and depth. For persuasive communicators, knowing the full breadth of one’s toolkit is essential to crafting sound arguments that move audiences.

Derived from classical antiquity, rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It rests alongside grammar and logic as the core pillars of structured communication. Most well-known from Aristotle’s development of the term, its tendrils are far reaching. From Cicero to Steve Jobs, rhetoric has been practiced by orators and executives alike and remains the framework for those seeking specific actions from their words.

However, much like the above-mentioned sword, rhetoric takes on the aims of whomever wields it. Where politicians have dragged its reputation through the mud with pandering or vitriolic speech, figures like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. have used its power to further civil rights in one of history’s shining moments. Like law or medicine, rhetoric is a set of neutral tools that are given shape through actions. Afterall, wouldn’t we consider mob lawyers and pro bono public defenders as both playing in the same sandbox? You be the judge.

To help shed further light, let’s explore some of the ways rhetoric is used to structure and sustain the power of persuasion. If it helps, consider divorcing rhetoric from its practitioners and hone your focus on the linguistic gymnastics at play in each example.

“We make out of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry.” – William Butler Yeats

Just how primates, people, and pachyderms classify as mammals, rhetoric also houses many subgroups. Under its umbrella are elementary terms like hyperbole, metaphor, and simile that should feel familiar. These devices help draw comparisons between like and differing things and foster connections within our writing and speech. Oftentimes these are among the first rhetorical tools learners acquire in their educational journeys. For developing minds, these devices can provide critical scaffolding to arrive at more complex knowledge and reinforce life-long learning.

More advanced terms like synecdoche, anadiplosis, and anthimeria may appear dense and off-putting until you see them in action:

Have you ever been referred to as the food you ordered at a restaurant? In that case, your server was using synecdoche to further that social interaction. While derogatory on its surface, “Who’s the meatloaf?” employs this rhetorical device by allowing a part (your order) to stand in for a whole (yourself). “Boots on the ground” and “Many hands make light work” are also common examples. If you’re interested, there’s a whole movie about how this can get wildly out of control.

This refers to using the end of one sentence to begin the next, and so on. If you happened to learn your skeletal anatomy with the age-old ear worm “Dem Bones” thigh bone connected to the hip bone / hip bone connected to the backbone then congratulations, you’ve successfully used anadiplosis to profound effect. Like the song, rhetorical devices can create powerful rhythms and cadences that serve as mnemonic devices for your audience.

Employed across time by Shakespeare and slang partitioners alike, anthimeria is a five-dollar term for using one part of speech for another. Think of it as verbing a noun (as in “Let’s table this discussion for another time”) or nouning a verb (as in “I’m useless without my morning run”). Few have employed anthimeria to greater effect than the Bard. However, it remains a site of evolution that keeps language usage in constant flux.

These are just some examples of rhetorical devices at play in the real world, with many so well-integrated they can pass by unnoticed. In fact, you’ve already read examples of alliteration, anthypophora, antonomasia, and dysphemism in this piece, perhaps without realizing it. And yet, knowing how to consciously deploy these techniques is akin to knowing one’s way around a toolbox. Understanding the function and purpose of a hammer, screwdriver, chisel, etc. ensures they’re used tactfully for maximum effect.

Along with setting up a firm basis of micro-level rhetorical devices, macro structural decisions of a talk or post are also key. Let’s explore how they can be used to convey authority and impact for effective communications.

“Wherever there is persuasion, there is rhetoric. And wherever there is ‘meaning’ there is ‘persuasion’” – Kenneth Burke

Beyond line-by-line usage, rhetorical choices also guide a speech or text operates on a structural level. In fact, taking a bird’s eye view of how language is presented is also a function of rhetoric. Determining slide order in a pitch deck to whether a meeting should be an email are all rhetorical choices. While there are untold reasons to arrive at a given approach, many fall into two buckets: connecting with your audience and enhancing the appeal of your message. To avoid putting the cart before the horse, consider your audience first.

Making an Audience Needs Map™ is a great jumping off point to begin understanding how to structure the major movements within your talk or piece. Key demographic indicators can help here, such as:

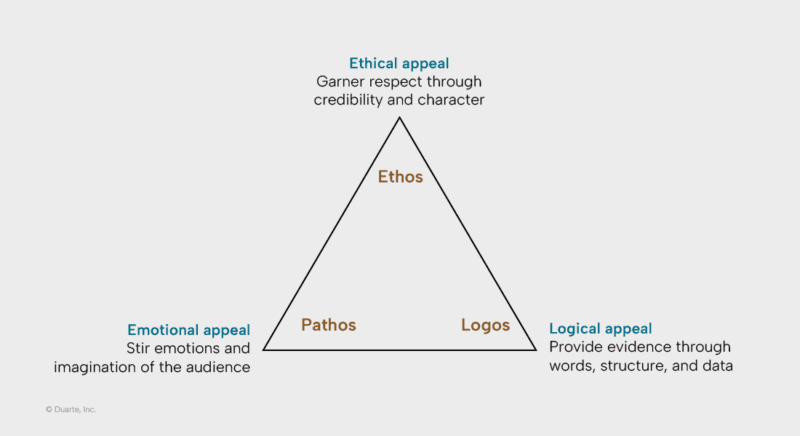

By answering these questions ahead of time, you’ll be better prepared to position your message within the three core elements of persuasion: ethos, logos, and pathos.

As biproducts of rhetoric, the concepts of ethos, logos and pathos define the overall tone of your message. Like a balanced diet, sound persuasion should take each point of the triangle into consideration for maximum appeal. To strike the right balance, it’s helpful to remember that these appeals are far from mutually exclusive. Therefore, your message should combine these appeals to find purchase across diverse audiences. Below are a few possible configurations to consider. At no point is a portion entirely ignored. Rather each is ranked in priority to meet specific audience needs.

Programmers or engineers may find appeals to analysis (logos) and credibility (ethos) most compelling, ignoring emotion (pathos) denies their humanity. However, as the image on the right-hand side illustrates, overextending an emotional appeal can risk your message appearing disingenuous or overly-saccharine to a more “serious” audience. This is also true in the other extremes as well. Too much analysis can become dry and off-putting, while excessive nods toward credibility may be perceived as a smokescreen to distract from possible red flags (the lady doth protest too much, methinks).

With this balancing act in mind, arriving at a formal structure that appropriately harnesses each appeal also involves proper foresight. A pervasive and effective rhetorical structure, the Sparkline, can buttress this need by illustrating what your audience stands to gain by adopting your Big Idea.

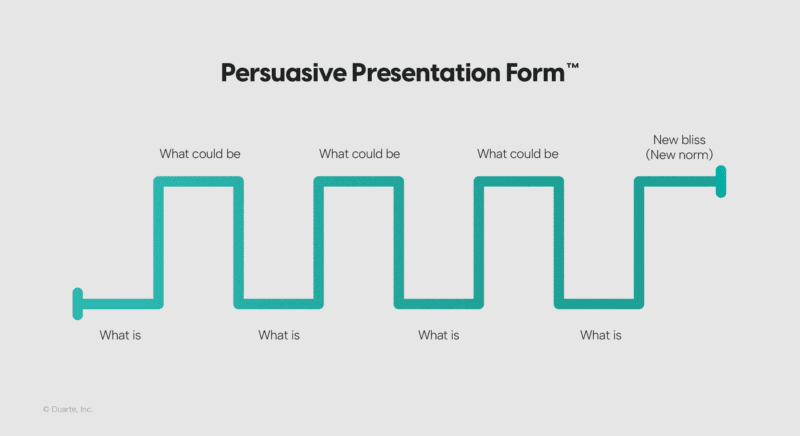

First identified by Nancy Duarte in her now infamous TED talk, the Sparkline is a rhetorical structure that pivots between a core binary within a talk to arrive at a desired outcome. By appealing to ethos, logos, and pathos, the speaker oscillates between describing the world as it is and how it could be if your Big Idea were adopted at scale. To reveal how a Sparkline works in practice, Nancy maps Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream Speech” alongside Steve Jobs’ 2007 iPhone launch to emphasize how the toggling throughout highlighted the speaker’s vision.

When illustrated, this Persuasive Presentation Form™ creates peaks and valleys of understanding that tighten into a coil as they move toward a “New Bliss.” This structure helps wind the audience’s perspective toward seeing this potential new world through the eyes of the speaker.

Once you’re working within the Persuasive Presentation Form™, micro-level rhetorical devices can come in handy to drive your audience’s understanding of the world as it could be. Dr. King used anaphora by repeating the phrase “I have a dream” to illustrate his hope of achieving racial harmony in America. Certain devices can even create this toggling in a single phrase. John F. Kennedy deployed a deft syntactical inversion known as chiasmus with the line “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country” to motivate an apprehensive populace toward putting astronauts on the moon. Whether taking the long or short road to imparting your vision, there’s always a rhetorical device to help with the heavy lifting.

But a persuasive presentation isn’t the only rhetorical structure for moving audiences to action. Telling an engaging story can also help guide listeners to envision your New Bliss as a possible reality. There are just as many ways to tell a story as there are rhetorical devices. To this end, the Three-Act Structure is a time-tested approach for communicating Big Ideas in a relatable format.

Star Wars. The Lord of the Rings. The Matrix. These are just some recent examples of stories that chart the transformation of a key main character: the hero. But tales of reluctant heroes becoming major change-makers date back to the primordial soup of oral tradition. In his groundbreaking work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell mapped the plotlines of myths and folklore to reveal the archetype of the Hero’s Journey that continues to resonate across popular culture. The Three-Act Structure can help distill the Hero’s Journey by abbreviating its movements into a trio of core components. However, when applying this format to a live audience or reader, they are the hero who must emerge transformed.

By framing your audience or reader as the hero, you’re giving them the agency to adopt your Big Idea and move from the world as it is to bask in the glory of your New Bliss. To achieve this, you’ll want to choose the right rhetorical devices that bridge understanding with your audience. As you encountered above, this can include metaphors, similes, hyperbole, or any number of techniques that produce the sentence structures and repetition you need to drive your message home.

Great writers are often prolific readers. Therefore, consider studying iconic speeches to help draw inspiration and cherry-pick effective flourishes for your talks. Learning the fundamentals can reveal the depth of your toolkit, while studying the works of others can sharpen your abilities. However, knowing when it’s time to formalize your education can go a long way toward building a strong rhetorical foundation. Thankfully, our academy offers in-person and on-demand opportunities to grow and refine your skills as an artful communicator.

“The arts of speech are rhetoric and poetry. Rhetoric is the art of transacting a serious business of understanding as if it were a free play of the imagination; poetry that of conducting a free play of the imagination as if it were a serious business of understanding.” – Immanuel Kant

For too long, rhetoric has been a dirty word. Its association with outdated modes of education and corruption by silver-tongued saboteurs have led its stock to suffer. From select vantage points, this is understandable. But as we discussed above, rhetoric is inherently neutral. Like laws and swords, rhetoric is corrupted by its use. There will undoubtably be those who misuse their influence. However, the potential to move and motivate through thoughtful rhetorical devices and structure is enough to resuscitate its potential for all who aim to build. And to those, Duarte has much to offer.

While we touched on a variety of freely available resources above, leaders looking to make a lasting commitment to their rhetorical prowess have a menu of opportunities at their disposal. Duarte training workshops on presentation writing, design, and delivery can help reorient your team’s appreciation and understanding of rhetoric as it applies to your organization’s success. From increasing your influence to reaching audiences and customers on a deeper level, training workshops will help you apply rhetorical decisions at scale. Taking time to upskill your team or entire departments is a terrific way to build camaraderie and maximize potential.

To learn more about how Duarte can help chart your rhetorical journey, book a call with a training concierge today to talk through available offerings. In a world steeped in messaging, embracing the power of persuasion can help yours rise to the top.