VisualStory®

Structure and storyboard a talk

Analyze your audience and organize your ideas into a story structure that will move them. Transform content into visual concepts and build a storyboard for your presentation.

Last night President Barack Obama delivered what could be considered the biggest presentation of the year. In outlining his vision for America and his legislative priorities for 2012, the President attempted to persuade a variety of different audiences – including the United States Congress, business leaders and 25 million members of the American public – that he has a plan to continue improving the lives of Americans.

So how did he do? Leaving aside the merit of his proposals, did he tell a story compelling enough to convince such a broad audience?

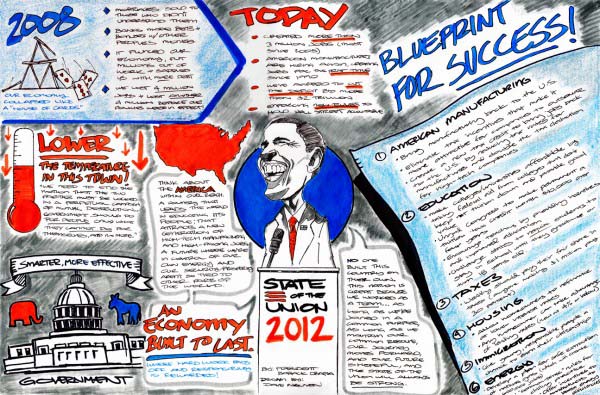

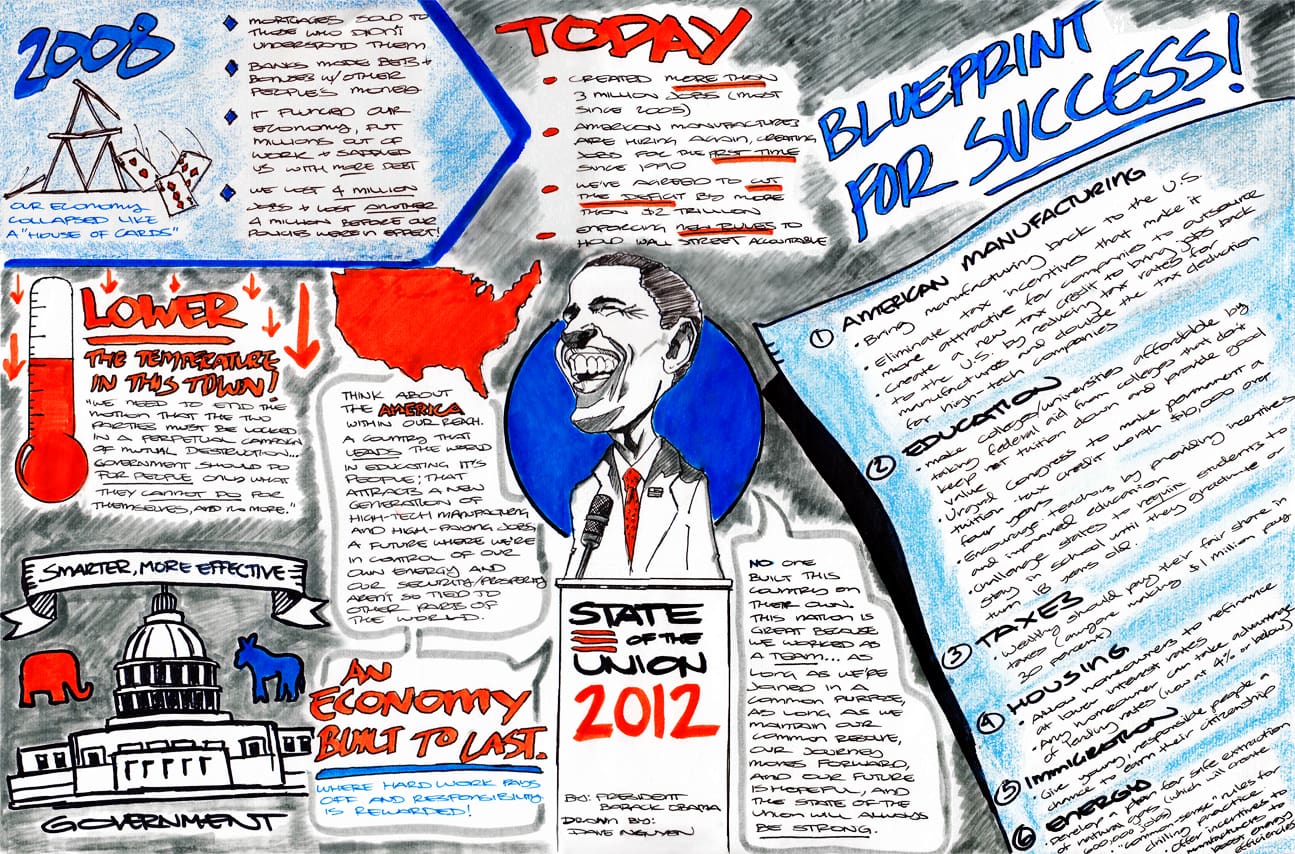

Graphic recording of the State of the Union address created by Duarte designer Dave Nguyen

President Obama used several valuable tactics to make his case. Rather than focusing only on statistics when trying to communicate employment figures or strategies to create jobs, he contrasted these statistics with stories of real Americans struggling to make ends meet. After pointing to “millions of Americans” who “are looking for work,” he talked about Jackie Bray, a single mother from North Carolina who found a new job after participating in a training program, and Bryan Ritterby, a man who lost his job in the furniture industry but now works for a wind turbine manufacturer. The president’s speechwriters clearly gave thought to how to personalize the hardships facing many Americans and how to suggest that the president is in touch with these struggles.

Interestingly, both President Obama and Governor Mitch Daniels of Indiana (who delivered the official Republican response) evoked the late Steve Jobs as an example of a job creator. Although the two men told very different stories about the role of government in job creation, their common allusion suggests that American cultural references don’t differ as much from Republican to Democrat as we may think.

President Obama also used several clever rhetorical tricks to make certain ideas stand out. He created contrast between “what is” and “what could be” should Congress take his suggested action. For example, he used this strategy when describing the tax code.

| “Right now, companies get tax breaks for moving jobs and profits overseas. Meanwhile, companies that choose to stay in America get hit with one of the highest tax rates in the world.” | “If you’re a high-tech manufacturer, we should double the tax deduction you get for making products here. And if you want to relocate in a community that was hit hard when a factory left town, you should get help financing a new plant, equipment, or training for new workers.” |

| What is | What could be |

Even his call to action contained this contrast by comparing what we need to “stop” and what we need to “start.” He used this type of language repeatedly throughout the speech to help reinforce his message that America’s “future is hopeful” if we move forward.

He also consistently used visual language and phrases meant to resonate and be repeated. When describing Washington partisanship the president said we have to “lower the temperature in this town” to end the “perpetual campaign of mutual destruction.” He evoked the ideas of historical figures like the “Republican Abraham Lincoln” to emphasize the possibility of uniting Washington and the country. And he played on the words of President John F. Kennedy when he challenged business leaders to “ask yourselves what you can do to bring jobs back to your country” and promised that “your country will do everything we can to help you succeed.”

President Obama saved the most memorable part of his speech for the close. But his S.T.A.R. moment for the night was also his biggest missed opportunity. In detailing his personal recollection of the mission to apprehend Osama Bin Laden, he constructed a striking metaphor for creating unity across America.

“Those of us who’ve been sent here to serve can learn from the service of our troops. When you put on that uniform, it doesn’t matter if you’re black or white; Asian or Latino; conservative or liberal; rich or poor; gay or straight. When you’re marching into battle, you look out for the person next to you, or the mission fails. When you’re in the thick of the fight, you rise or fall as one unit, serving one Nation, leaving no one behind.

One of my proudest possessions is the flag that the SEAL Team took with them on the mission to get bin Laden. On it are each of their names. Some may be Democrats. Some may be Republicans. But that doesn’t matter. Just like it didn’t matter that day in the Situation Room, when I sat next to Bob Gates – a man who was George Bush’s defense secretary; and Hillary Clinton, a woman who ran against me for president.

All that mattered that day was the mission. No one thought about politics. No one thought about themselves. One of the young men involved in the raid later told me that he didn’t deserve credit for the mission. It only succeeded, he said, because every single member of that unit did their job – the pilot who landed the helicopter that spun out of control; the translator who kept others from entering the compound; the troops who separated the women and children from the fight; the SEALs who charged up the stairs. More than that, the mission only succeeded because every member of that unit trusted each other – because you can’t charge up those stairs, into darkness and danger, unless you know that there’s someone behind you, watching your back.

So it is with America. Each time I look at that flag, I’m reminded that our destiny is stitched together like those fifty stars and those thirteen stripes. No one built this country on their own. This Nation is great because we built it together. This Nation is great because we worked as a team. This Nation is great because we get each other’s backs. And if we hold fast to that truth, in this moment of trial, there is no challenge too great; no mission too hard. As long as we’re joined in common purpose, as long as we maintain our common resolve, our journey moves forward, our future is hopeful, and the state of our Union will always be strong.”

This story was powerful because of its personal nature but also because of the themes of commonality and the powerful visual imagery he used.

But this message could have been even more impactful had he built on it throughout the speech. The best presentations have a common theme or message, a purpose that we at Duarte often call the “throughline.” Although the president’s address was powerful in pieces, it often lacked a common overarching theme to tie the elements together. While he may have intended to create this throughline by introducing the military as an example of unity in the beginning, this common message was often lost in the bulk of his words.

Audience members who viewed the “enhanced content” online may have had similar thoughts. Although the president avoided some of the worst PowerPoint crimes – he generally avoided bulleted slides and he made good use of statistics by not overwhelming the viewers with information – the materials lacked a common visual theme and did not always take advantage of the images painted by his powerful words.

President Obama did a lot right last night. When picked apart, sections of his address resonate with the type of language that good writers challenge themselves to craft. But as a whole, the 2012 State of the Union needed a good dose of the unity that the president challenged the nation to create.

To view last night’s State of the Union, visit:

http://www.whitehouse.gov/

You can also find the “enhanced content” on SlideShare at:

http://www.slideshare.net/whitehouse/state-of-the-union-enhanced-graphics

The Republican Response is available at:

http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=7396293n